Explore the definition, theories, major historians, and key periods of world history. Understand how historical events have shaped civilizations and influenced modern society.

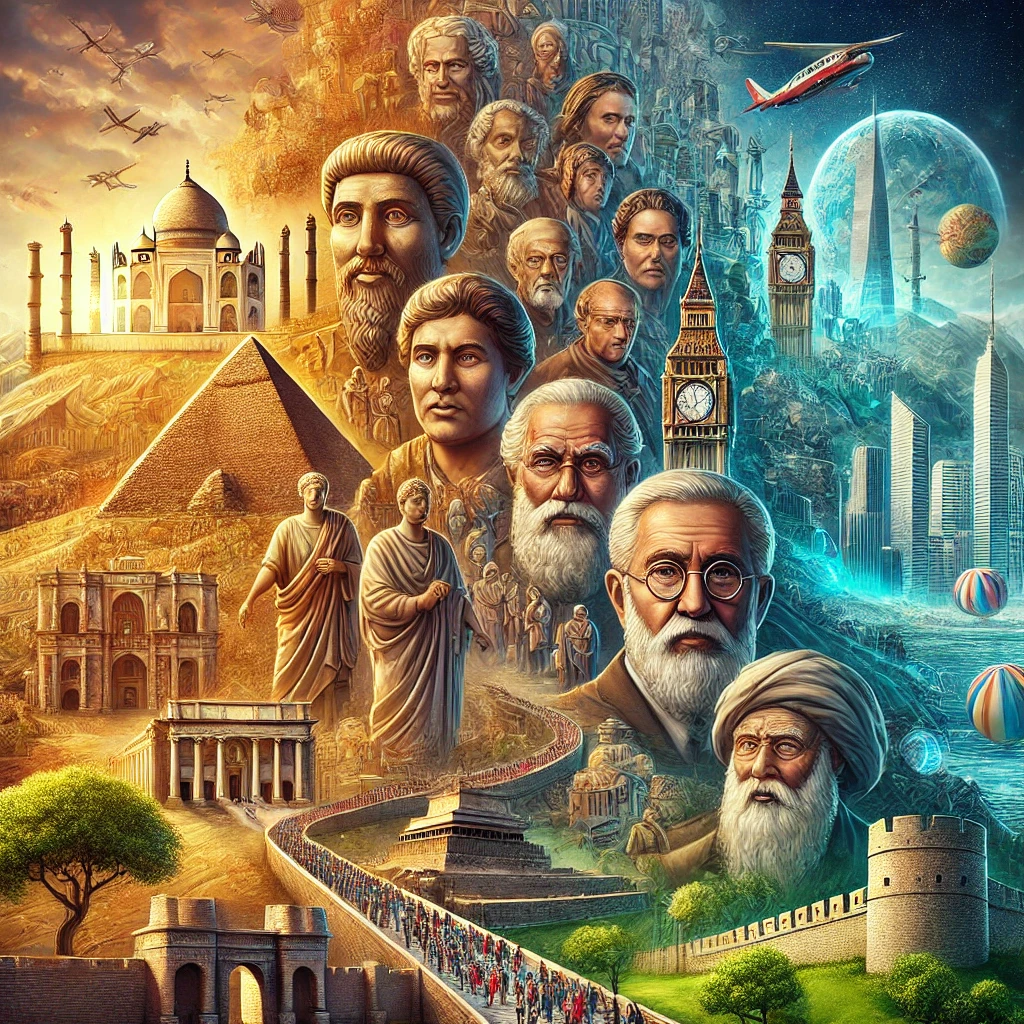

Introduction to World History

World history is the study of the past on a global scale, encompassing the development, interactions, and transformations of societies and civilizations. It provides a comprehensive view of how human societies have evolved, from ancient times to the modern era, considering economic, political, social, and cultural influences. By analyzing historical events, scholars can understand the patterns that have shaped human civilization and gain insights into contemporary global issues.

Definition of World History

World history is a broad discipline that explores historical events and trends beyond national or regional boundaries. It investigates the interconnections between civilizations, including trade, migration, war, and cultural exchange. Historians focus on major themes such as imperialism, globalization, technological advancements, and social movements to paint a picture of human progress over millennia.

Theories of World History

World history is interpreted through various theoretical frameworks that help historians analyze past events and societal changes. Some of the most influential theories include:

The Great Man Theory

The Great Man Theory, proposed by historian Thomas Carlyle, suggests that history is shaped by the actions of influential individuals. According to this perspective, figures such as Alexander the Great, Napoleon Bonaparte, and Mahatma Gandhi played a pivotal role in shaping the course of history. Proponents of this theory argue that leadership, charisma, and individual vision drive historical change rather than broader societal forces. Critics, however, believe that this theory oversimplifies history by ignoring economic, social, and cultural influences that also contribute to major historical events.

Marxist Theory of History

Developed by Karl Marx, the Marxist Theory of History posits that economic structures and class struggles drive historical change. According to this theory, history progresses through a series of conflicts between different social classes—particularly between the ruling class (bourgeoisie) and the working class (proletariat). Marxist historians argue that the transition from feudalism to capitalism and eventually to socialism follows a predictable pattern based on economic forces. This theory has influenced many historians and political movements, although critics argue that it overlooks cultural and ideological factors that also shape history.

Cyclical Theory of History

The Cyclical Theory of History suggests that civilizations rise, experience a golden age, decline, and eventually collapse, only to be replaced by new civilizations that follow the same pattern. This theory is supported by examples such as the rise and fall of the Roman Empire, the Chinese dynastic cycle, and the collapse of the Mayan civilization. Some historians argue that this theory helps explain long-term historical trends, while others believe that it lacks predictive power and ignores unique historical circumstances that can influence a civilization’s trajectory.

World-Systems Theory

A considerably more complex scheme of analysis, world-systems theory, was developed by the American sociologist and historian Immanuel Wallerstein (1930–2019) in The Modern World System (1974). Whereas modernization theory holds that economic development will eventually percolate throughout the world, Wallerstein believed that the most economically active areas largely enriched themselves at the expense of their peripheries. This was an adaptation of an idea of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin (1870–1924), the leader of the Bolshevik Revolution (1917), that the struggle between classes in capitalist Europe had been to some degree displaced into the international economy, so that Russia and China filled the role of proletarian countries. Wallerstein’s work was centred on the period when European capitalism first extended itself to Africa and the Americas, but he emphasized that world-systems theory could be applied to earlier systems that Europeans did not dominate.

Consistently with Wallerstein’s view, the German-born American economist André Gunder Frank (1929–2005) argued for an ancient world system and therefore an early tension between core and periphery. He also pioneered the application of world-systems theory to the 20th century, holding that “underdevelopment” was not merely a form of lagging behind but resulted from the exploitative economic power of industrialized countries. This “development of underdevelopment,” or “dependency theory,” supplied a plot for world history, but it was one without a happy ending for the majority of humanity.

Like modernization theory, world-systems theory has been criticized as Eurocentric. More seriously, the evidence for it has been questioned by many economists, and, while it has been fertile in suggesting questions, its answers have been controversial.

A true world history requires that there be connections between different areas of the world, and trade relations constitute one such connection. Historians and sociologists have revealed the early importance of African trade (Christopher Columbus visited the west coast of Africa before his voyages to the Americas, and he already saw the possibilities of the slave trade). They have also illuminated the 13th-century trading system centring on the Indian Ocean, to which Europe was peripheral.

Humans encounter people from far away more often in commercial relationships than in any other, but they exchange more than goods. The Canadian-American historian William H. McNeill (1917–2016), an eminent world historian, saw these exchanges as the central motif of world history. Technological information is usually coveted by the less adept, and it can often be stolen when it is not offered. Religious ideas can also be objects of exchange. In later work McNeill investigated the communication of infectious diseases as an important part of the story of the human species. In this he contributed to an increasingly lively field of historical studies that might loosely be called ecological history.

Cultural Diffusion Theory

Cultural Diffusion Theory examines how cultural ideas, technologies, and practices spread from one civilization to another. This diffusion can occur through trade, conquest, migration, or communication. For example, the spread of writing systems, religious beliefs, and scientific knowledge from Mesopotamia to other parts of the world exemplifies cultural diffusion. Historians use this theory to explain how innovations and ideologies have shaped human societies across different time periods. However, some critics argue that it does not fully account for indigenous development and resistance to external influences.

Modernization Theory

Modernization Theory suggests that societies progress through a series of stages from traditional to modern structures. This theory emphasizes industrialization, technological advancement, and economic growth as the key drivers of historical development. It argues that underdeveloped nations can achieve modernization by following the models of industrialized Western nations. The theory became popular during the Cold War as a justification for capitalist economic policies and democratic governance. However, critics argue that it oversimplifies historical development by assuming a universal path for all nations, ignoring cultural differences, and underestimating the impacts of colonialism and global inequalities.

Key Historians in World History

Several historians have significantly contributed to the study of world history. Their works have shaped historical understanding and interpretation across various eras:

Herodotus (484-425 BCE)

Known as the “Father of History,” Herodotus was an ancient Greek historian who wrote The Histories, a comprehensive account of the Greco-Persian Wars. His work is notable for its systematic gathering of information and attempt to explain historical events through a mixture of eyewitness accounts and storytelling. While some of his narratives contain mythical elements, his approach laid the foundation for historical inquiry.

Thucydides (460-395 BCE)

A contemporary of Herodotus, Thucydides is regarded as the first true historian due to his reliance on empirical evidence and critical analysis. His work History of the Peloponnesian War provides a detailed and objective account of the conflict between Athens and Sparta, emphasizing political and military strategies. His emphasis on rational analysis over divine intervention set a precedent for future historical scholarship.

Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406)

An influential Arab historian and philosopher, Ibn Khaldun is best known for Muqaddimah, a groundbreaking work that introduced the concept of historical cycles and sociological factors in history. He proposed that civilizations undergo predictable patterns of rise and decline, shaped by social cohesion, economic structures, and leadership dynamics. His theories remain relevant in modern historiography.

Edward Gibbon (1737-1794)

Gibbon’s monumental work The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire explored the reasons behind the collapse of Rome. His analysis, which included the role of Christianity, military overextension, and internal decay, remains a cornerstone of historical study. Gibbon’s emphasis on primary sources and his eloquent prose make his work a classic in world history.

Leopold von Ranke (1795-1886)

Ranke is often credited with professionalizing history as an academic discipline. He promoted the use of primary sources and an objective, scientific approach to historical writing. His works on European history set new standards for historiography and inspired later historians to adopt rigorous research methods.

Arnold J. Toynbee (1889-1975)

Toynbee’s A Study of History analyzed the rise and fall of civilizations through a challenge-response framework. He argued that societies thrive when they successfully respond to challenges but decline when they fail to adapt. His comparative approach made significant contributions to the study of world history, though some critics believe his theories are too deterministic.

Yuval Noah Harari (b. 1976)

A contemporary historian, Harari gained international fame with Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. His work examines world history through an interdisciplinary lens, incorporating anthropology, biology, and economics. Harari’s writings challenge traditional narratives and explore themes such as human cognition, technological revolutions, and globalization.

Conclusion

World history is an essential field that connects humanity’s past, present, and future. By examining patterns, theories, and major events, we gain a broader understanding of how civilizations have shaped the world. Whether through trade, war, innovation, or cultural exchange, world history remains a key discipline for understanding the human experience.

Read More Articles

Heritage Film receives multiple awards in an international competition

Leave a Reply